In the Gürtel, nobody can hear you scream (in a good way).

WHAT DO YOU DO WHEN YOU WANNA ROCK, but your neighbors upstairs would prefer you… not? If you’re Othmar Bajlicz, music lover, former Austrian footballer, and founder of Vienna music venue Chelsea, you don’t venture to the other side of the tracks—you go underneath them.

Specifically, you move your popular club from a residential building in District 8 into the arches of a viaduct in Vienna’s Gürtel, defined by the massive arterial ring-road separating the city’s inner districts from the suburbs (gürtel is German for belt). Here, tucked under the U6 U-Bahn and flanked by heavy traffic, no one complains about the noise. No one can even hear you. The trains chugging overhead are not only unbothered by the amplified bass, on occasion they get into it, rattling some beer glasses of their own.

While in hindsight Chelsea’s current location is ideal for a rambunctious music venue, it took some time to get there—including a lawsuit, and, over three decades ago when the Gürtel was a less than desirable area, a bit of courage. But in Bajlicz, Chelsea had an owner who was all in. Retired from soccer at the ripe age of 30, he set his sights on music, and opened the first iteration of Chelsea in 1986. He had a vision, and the club filled a much-needed niche. Vienna’s live music scene was sparse and homogeneous, and there was often a cover price. In a city devoid of places where music lovers, writers, and editors could simply congregate, Chelsea promised to be their Cheers.

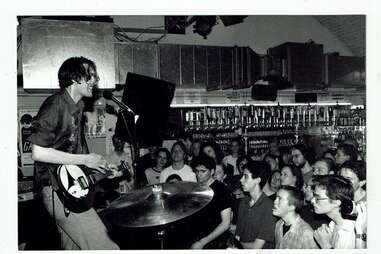

Bajlicz booked both DJs and bands, and served some Anglophilic offerings on tap. (Though it’s often associated with the British football team, it was in fact named after the London neighborhood where punk was born.) A music magazine was created in conjunction with the space. The original Chelsea hosted bands with amazing names like Pungent Stench and Fetish 69, and once it gained international notoriety, attracted the likes of Die Toten Hosen and a little up-and-coming outfit called Soundgarden.

But not everyone was so enthusiastic about its arrival. “People lived in the building,” says Bajlicz. “We had problems with the neighbors about the noise, especially with the live music.” Because of complaints, concerts were whittled down to once a week. After a court case, the space eventually closed and the team was forced to relocate.

At the same time, Vienna’s administration was trying to clean up a rundown area that had become the city’s red light district. They offered Bajilcz an open-ended tenancy agreement in exchange for a space nobody else wanted. In 1995, the second incarnation of Chelsea opened its doors in the Gürtel, and quickly picked up where it left off. It also kickstarted a trend, becoming the first of many bars and venues to move into the once disparaged area, forming what today is widely considered one of Vienna’s most vibrant, thriving nightlife areas: a true metropolitan success story. The arches under the viaduct became so popular that they later attracted another set of arches: a pair of golden ones, attached to a bi-level McDonald’s, which comes in pretty handy after a night out.

THINK OF VIENNA AS A CELL. In the nucleus is the old medieval city, once a camp for the Roman Empire, later the center of the European universe under the Austrian Habsburgs. Here you’ll find your (multiple) museums, your classical music venues, and your Spanish Riding School. There’s high-end shopping streets and, in the winter, a host of traditional Christmas markets. It’s the country’s administrative, political, and economic center, with buildings like the Austrian Treasury and the gorgeous St. Stephen’s Cathedral open for perusal. Once walled in, this historical core—the Innere Stadt, or District 1 of Vienna’s 23 geographical designations—is where tourists are most likely to gravitate. And it’s easy to know its limits: where the old town walls once stood is now the famous Ringstraße, or ring road.

There was once another fortified wall sectioning off sections of the city. While the Ringstraße created an inner pocket for the church and the ruling class, its prominent boulevard a stage for powerful actors, a concentric outer wall held the businesses, suburbs, and proletariat. After it was demolished, in 1873 its site became the Wiener Gürtelstraße—colloquially, the Gürtel— a major thoroughfare utilized by the backbone of the city.

Endorsed by Freddie Mercury.

In the late 1800s, an almost fully elevated railway was added to the Gürtel to shuttle even more bodies to and from the city’s industrial ring. The powers that be opted to model the tracks after a Roman viaduct, both functionally and aesthetically. From the beginning, they envisioned leasing the arched spaces below, which ranged from one to three floors depending on height fluctuation, out to local businesses. Leading Viennese architect Otto Wagner—a founder of the Secession Movement—was enlisted to execute the vision; he designed the semicircular openings with transparent enclosures for passersby to peer directly into the commerce.

As planned, shops and other businesses moved into the ground floor lots and the area thrived. But then came WWII, when many of the glass facades were shattered or sealed in for cover. The viaduct started to resemble a wall, once again creating a partition in the city. As merchants left, less and less people came around. At the same time, automobile culture exploded, and the Gürtel was widened to eight busy lanes to accommodate the influx of cars. In their wake came rampant exhaust pollution and noise, abandoned storefronts, and social degradation—an unattractive landscape for anyone looking for a smogless, chaste urban adventure. But perfect for a red light district. And also music venues. And the eventual attempt to turn the area around.

WHICH BRINGS US TO CHELSEA. To be clear, sex work is legal in Austria (for the most part), but while there’s no official red light district, establishments are concentrated in certain areas, including within the northern Gürtel. In this particular strip, however, it’s all about the music.

You’d be forgiven for not knowing what you might encounter behind Chelsea’s doors. Unlike many of its neighbors, with their arched facades once again featuring transparent glass—all the better to lure you in by what’s inside—from its exterior, Chelsea is a mystery, save for the countless music posters taped to the windows. And stepping inside doesn’t really clear things up, either. You’re greeted by a bar brimming with booze and slapped with stickers. On a mounted television, a soccer game plays unceremoniously. There’s sports paraphernalia scattered about—miniature team pendants, vintage photos of matches.

And he’s not kidding. They throw about 200 concerts each year, typically favoring Britpop and punk. But just like Bajlicz, the venue also has a sporty side. “We also show football games from all the main European Leagues,” he adds. “English Premier League, Italian Serie A, Spanish La Liga, German Bundesliga, and Austrian Bundesliga.” If none of that appeals, there’s also pop culture-themed pub trivia.

When the weather’s nice, outdoor tables allow crowds to spill onto the street, butting up against the several other venues that have set up shop since Chelsea proved the area viable. There’s the relaxed Loop, with free admission, music, schnitzel, and cocktails, and rhiz, its glass doors broadcasting electronica aspirations to the street. B72 is a bi-level live music hotpot, hosting budding alternative acts and the occasional emo night.

Each new arched doorway provides another opportunity for a good night out. The modern Halbestadt Bar has consistently been called out as one of the best places in town to enjoy a tipple. There’s Coco Bar, a music venue where you can also catch a football game, dance clubs like [kju:], the world music-heavy Fanialive, and the Loft, which ranges from raucous parties to sedate poetry nights. The Kramladen does a little bit of everything, including comedy nights, while Café Carina’s free offerings run the gamut from rock to open mics. Want food? Just a few steps from Chelsea sits the sleek gastropub Gürtelbräu, its brick arches and soft lighting making it a choice date night destination.

And just a few blocks away, past some greenery, you’ll find what is possibly the most aesthetic McDonald’s you’ve ever seen. You could have a pretty good time there too—it, like all Austrian McDonald’s franchises, serves beer alongside delicious-looking pastries. Not that Bajlicz would know. “I was not surprised when the McDonald’s moved in,” he says. “But I don’t go there.”

Source : Thrilist