There is rather more than meets the eye to Emmanuel Macron’s inept visit to Beijing last week. The immediate fallout – Xi’s flat refusal to change tack on Ukraine, and Macron’s subsequent insistence that France was not beholden to the US or for that matter over-concerned with what China might do in Taiwan – looks like a stinging national rebuff to France and a face-saving retreat by Paris to curry favour with China. And so it is. But it goes further. There is a strong EU dimension to this whole debacle: what it really shows is the increasing weakness and disunity of Europe when it tries its hand at power projection on the world stage.

The important point is that the negotiations with Xi were not a purely French affair, but also very much an EU operation. Macron did not go to Beijing alone: he was accompanied by Ursula von der Leyen, who fairly explicitly added Europe’s weight to the unsuccessful request to Xi to abandon his covert support for Russia. Furthermore, shortly after the event Charles Michel, the European Council president who can normally be trusted to faithfully express the view of the Brussels nomenklatura, expressed a surprising degree of support for Macron’s statement. He carefully referred to European leaders’ increasingly favourable attitude towards Macron’s expressed idea of ‘strategic autonomy’ away from the United States.

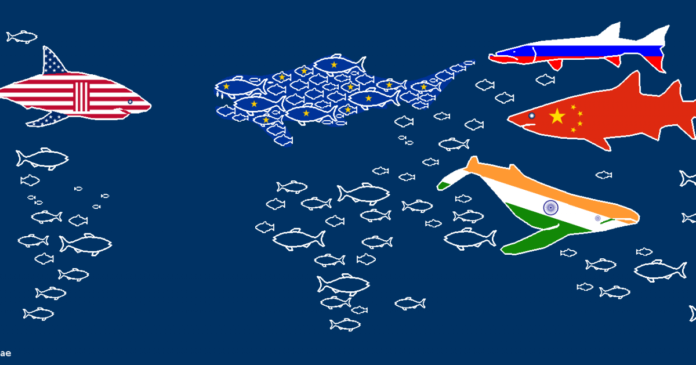

These points matter, since three things follow from them. One is that, since Xi’s rebuff was as much addressed to the EU as to France, any EU pretensions to act as an axis of soft power between China and the US are now very significantly weakened. If Xi is happy to bat off like a tiresome fly a pointed threat from Brussels, this does not say much for Europe’s much-vaunted diplomatic clout as an economic, though non-military, heavyweight.

The second is that Brussels is pretty clearly signalling that it prefers quiet relations with China to being seen to take sides over Taiwan. Charles Michel’s specific caution over the idea that Europe should ‘systematically follow the position of the United States on all issues’ looks very much like a coded statement that it rather supports the attitude of France and, for that matter, Germany (which has a large stake in keeping Beijing sweet: VW alone has 33 Chinese plants, producing some five million cars a year). Wherever Taipei does look for help, its chances of finding it in western Europe are not promising.

The third is that one should be increasingly sceptical of claims to European unity on matters of this kind. At the same time that Brussels was apparently nailing its colours to the mast with the agreement of the old EU countries, Poland was making its view quite clear. Just before flying to America for talks with the Vice-President, premier Mateusz Morawiecki took a carefully-calculated side-swipe at Macron. As far as he was concerned, close ties of cooperation with the US were the ‘absolute foundation’ of Europe’s security. ‘Instead of building strategic autonomy from the United States,’ he said, ‘I propose a strategic partnership with the United States.’ Nor was he alone. Numerous unnamed but exasperated eastern European diplomats, one suspects largely from the Baltic states, were also extremely outspoken about what they saw as France’s grandstanding, expressing disgust at the idea that people in Europe should see the positions of China and the US as in any way equivalent, and emphasising that it was time for democracies to stand together. With views like this from the EU states with actual experience of standing up to illiberal regimes, the ides of Europe speaking with one voice on the matter of geopolitics seems more a pipe-dream than ever.

What all this may well presage is the emergence a new way of doing international business in Europe. The traditional practice, under which a nod from the chancelleries of Berlin, Paris and Brussels would effectively dictate the public attitude of the bloc, has not worked enormously well (witness, for example, the EU’s rather clumsy efforts in the ex-Soviet bloc, which now risk sucking it into the conflict between arch-enemies Armenia and Azerbaijan). With the countries of eastern Europe, many of which have very different priorities and international moralities from Brussels, now more open about their own positions, its chances of survival are almost nil. States such as Poland, growing economically compared to the increasingly stagnant nations of the west and now aspiring openly to being the leading military power in the EU, are likely to lead by persuasion and example. If Brussels does not take this hint, preferring to invoke the official EU commitment to a common foreign and security policy, it will increasingly become irrelevant.

In the internal politics of the EU we have increasingly been seeing the political centre of gravity move eastward. It now seems extremely likely that we will see the same thing happening as regards its external affairs. The cosy, predictable EU that we have known for the last 30 years or so is fast vanishing before our eyes; we, and Brussels, had better get used to it.

Source : Spectator