Stuart Heritage

When the cola brand launched a points-for-prizes scheme in the 90s, John Leonard spotted a loophole and fought for what he saw as rightly his: a Harrier jump jet. A new documentary tells the wild story

In 1996, PepsiCo – then known for creating the young, cool, carbonated drink of a generation – made an incredible mistake. The company had just launched its Pepsi Points scheme, in which customers could save Pepsi labels and redeem them against Pepsi-branded merchandise. Sixty tokens would get you a hat. Four hundred and you’d get a denim jacket. But in the commercial accompanying the launch, Pepsi went further, joking that anyone who collected 7m labels would be eligible for a brand new Harrier jump jet. The mistake? Pepsi forgot to add any small print pointing out that it was a joke.

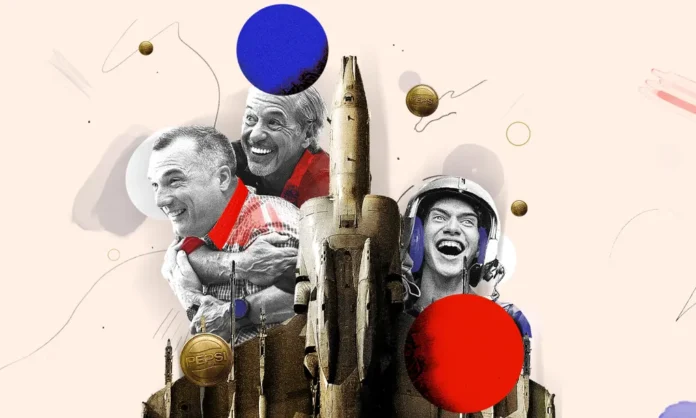

That one oversight now forms the basis for a wildly entertaining Netflix series, entitled Pepsi, Where’s My Jet? It tells the story of John Leonard, a Washington State community college student who decided to take Pepsi at its word. After quickly realising that buying 7m cans or bottles of Pepsi would be prohibitively expensive, Leonard saw a disclaimer revealing that, rather than collecting labels, consumers could buy Pepsi Points for 10 cents each. A $23m Harrier jump jet for just $700,000? That was the bargain of the century. Over four episodes, the show recounts one young man’s determination to take on a multinational corporation to get what an advert had promised him.

“John had this kind of Spielbergian quality about him when he was younger where it was just, like, anything is possible,” recounts Andrew Renzi, the show’s director, over a riotous four-way Zoom call with Leonard and Todd Hoffman (more on him later). “I don’t know if you have ever seen the film Being There,” Renzi adds, referring to the Peter Sellers satire about a gardener who accidentally works his way into the corridors of power, “but I had this thing in my head where John Leonard at 19 years old is Peter Sellers.”

“Yeah. So that’s pretty close to accurate,” Leonard interrupts.

Renzi sighs. “I forgot to mention that John is opinionated,” he says.

Renzi was initially offered Pepsi, Where’s My Jet? as a work of fiction. But after tracking down Leonard, by then in his mid-40s and working as a park ranger in Alaska, he realised that the truth would be more entertaining.

“It was a long time ago,” Leonard continues. “And I just kind of wanted to keep it back there, as something funny that happened a long time ago.” That changed when the Netflix series Tiger King became a lockdown hit, and people started looking for more weird historical stories to turn into documentaries; various producers came sniffing around. “There were some real schmucky people that would lay on this really thick, used-car salesman, Hollywood type of thing. But Renzi sent me an email. And of all the different emails I got, it felt really sincere. It didn’t seem like it was the same old thing of, you know, blowing smoke up your ass. But simultaneously, Todd and I had a conversation. He said something along the lines of: ‘This is a cool story. It needs to be told, and it needs to be told by the right person.’ He said: ‘When I die, I’d be happy to have this be on my epitaph.’”

Now let’s introduce Hoffman, the secret sauce of the whole crazed scheme. A charismatic millionaire, then in his 40s, Hoffman had befriended Leonard on a mountaineering trip. And when Leonard realised he needed $700,000 to force a fighter jet out of a fizzy drink company, Hoffman was the first person he turned to. To everyone’s surprise, Hoffman was keen.

“John brought this to me, and told me the story,” he recalls. “We looked at the videotape of the commercial, and I just kept looking at it over and over and over and going: ‘That is absolutely a reckless ad put out there by a major corporation that knows better.’” After that point, the game was afoot. Pepsi’s defence throughout was that the ad was clearly a joke. At one point during the series, a Pepsi spokesperson mentions that, while millions of people watched the advert, only one person actually tried to redeem the jet offer. It is possible nobody else went as far as Leonard in their attempts to claim the prize, but he points out that he first heard of Pepsi Points when a father at the Little League baseball team he coached mentioned he was part of a jet-buying consortium. Leonard was unique in being the only viewer who had access to Hoffman, a like-minded renegade with the funds to back it up.

John was the Pepsi generation. They blew a great opportunity to lasso this kid

JOHN LEONARD

Leonard describes Hoffman as “the math that Pepsi didn’t do. They were counting on there being a ton of dreamers like me, but they just never figured a dreamer like me would ever have access to somebody that was willing to go on this crazy ride and actually would write the cheque.”

“Making the series, I always had this guiding post of: ‘Everybody needs a John and everybody needs a Todd,’” Renzi explains. And it is this relationship, between two men of different generations who had a wild idea and saw it through, that runs through the series like a golden cord. Even decades later, over Zoom, they are warm and familiar, crashing into each other’s stories and finishing each other’s sentences.

“I just love being connected with people like John,” beams Hoffman. “He looks all serious and he looks conservative, but he’s insane. He’s certifiably insane. He holds a job. He has a beautiful family. He has a house and pays a mortgage and goes to work every day, but he’s got some real mental things going on. Way outside the box.”

The climax of the story is easily Googleable, but the journey there is about as crazed as its genesis. At one point, Michael Avenatti – later to find infamy as the lawyer of Stormy Daniels – pops up to help the fight against Pepsi, sharing a hotel room with Leonard in what is described as a “Planes, Trains and Automobiles road trip across the midwest”. Avenatti filmed his segments for the show under house arrest for attempting to extort Nike for up to $25m (he has since been imprisoned for defrauding Daniels), but his participation in the case was a rare point of contention between Hoffman and Leonard. While Leonard developed a personal friendship with Avenatti, Hoffman rankled at his methods. “I didn’t think of him as a major part of our story,” he says when Avenatti’s name is mentioned.

You sense that Pepsi is still embarrassed by the skirmish. The fight for the jet did the company no favours whatsoever. At the time it was still locked in the “Cola Wars” with Coca-Cola – a ruthless scrap for dominance that saw Pepsi introduce blind taste tests to prove its superiority to the world – and any slip-up could have been fatal. Here was a brand selling itself on how cool and youthful it was, but it responded to Leonard’s claim by – spoiler alert! – slamming him with teams of corporate lawyers. When TV companies saw what an open, guileless boy Leonard was, asking politely for his jump jet, he was suddenly everywhere. It was a terrible PR move from Pepsi, and Hoffman is still convinced that its self-inflicted damage lingers.

“John was the all-American kid,” he says. “He was the Pepsi generation. And that’s kind of what’s ironic, too. Pepsi blew a great opportunity to lasso this kid and say: ‘Look, we’ll take you around the country in the Harrier jet for the next year, we’ll pay you a million bucks.’ Instead of hiring lawyers and suing us, they could have actually done the right thing and said: ‘This kid put the deal together. He rang the bell and he gets the prize,’ you know?”

Still, this all happened a quarter of a century ago. The world has moved on. Leonard and Hoffman have changed. As we wrap up, I ask if it’s strange for them to revisit the distant past like this, knowing all the attention the show will bring.

“Over the years I’ve been sensitive to it, because even close people have said: ‘Well, you’re an opportunist,’” Leonard explains. “Lawsuits like this end up being compared to the McDonald’s hot coffee case, the kind of ambulance-chaser thing. And that hit me wrong. Looking back on it, it was opportunistic. Absolutely. But that’s not always a negative thing. And back then I wholeheartedly thought that we were going to get the jet.

“What I struggle with today,” he adds, “is how can I have really thought that I was going to get the jet? I’m 48 years old now, and I’m now looking back on it like: what kind of dipshit were you, man?”

Pepsi, Where’s My Jet? is on Netflix from Thursday

Source : The Guardian